Tell me if this sounds familiar. After a long day at the office - probably poring over the findings of a complex and detailed piece of research you've spent weeks working on - you find yourself at home trying to unwind. If you're like me then unwinding usually involves scouring through the TV channels - hopping left and right - in the search for something that fits that happy balance of vaguely interesting but not deeply engaging - just enough so you can switch yourself off.

The other night however, as I was bouncing from one station to the other, something caught my attention. It wasn't the latest happenings in a reality show or even the latest 'must-watch' that's been buzzing around the office; it was, quite simply, an advert. Usually I wouldn't pay much attention but due to the lack of anything else to focus on my brain was piqued by something they were saying.

The advert in question was for a well-known optician who were promoting a pair of glasses with a special optical lens to combat the glare of traffic lights when driving at night. But what caught my attention wasn't the product itself, it was the messaging that came with it - messaging in the form of a number of research statistics supporting the value of the new lenses.

“Based on a consumer survey conducted with 105 existing lens wearers, 85% agreed they felt less concerned about headlight glare when driving at night with our lenses.”

“LENSES FOR EVERYDAY USE AND SAFER DRIVING*”

*Based on a wearer trial with 100 participants conducted by Aston University. 67% agreed or strongly agreed they would recommend these lenses for everyday use.

Now while I don't doubt the voracity of the research, my experience of conducting research gave me a bit of insight which allowed me to question some of the things around these claims.

The first issue is around the size of the sample. While research can be reasonably conducted with smaller samples the results, and any statements of fact pulled from them, should always be shown in conjunction with the representative quota of the sample. Here we see that they've taken the results from existing users of the glasses which slightly skews the perspective of the research. Would non-users have so strongly advocated for this product in a similar trial?

These sorts of quasi-research findings are nothing new in advertising. You can find similar 'studies' propping up the marketing straplines on a number of products, from shampoo to skincare regimes, toothpaste and even sports and nutrition drinks. All of them exhibit the same sort of skewed representation to support whatever angle they're trying to pursue. And I'm not saying that market research has no place in advertising; it's just that the misleading and questionable positioning of these studies represents a wider malaise about market research in general.

It's probably not hard for anyone in our industry to cast their minds back over the past two years and recall the scorching criticism that researchers received in the aftermath of the General Election and the previous EU referendum. The scorn piled on for our industry's lack of ability to predict the outcome of these events was also set against a backdrop of people in the public eye advising everyone to "not trust the experts".

And it's this last part which goes to the heart of the issue for me. While we, as an industry, have always demonstrated our integrity by maintaining impartial and unbiased insight, often backed up with empirical data, there greater, and less frequently articulated, value that we rely upon as researchers; the value of trust.

For the work of market researchers to matter, not only to us but the people it is used to serve, then there needs to be an implicit trust in what we do. It is an essential component both now and in the future, if our industry is to continue to grow and be sustainable. The misappropriation of market research by advertisers serves to devalue the work of our industry - not directly or purposefully, but by creating a background hum of quick facts and figures which, with even a quick glance, only really devalue the authenticity of both the research and the product. If we as researchers cannot see that truth then we're truly myopic; and no amount of miraculous glasses with special lenses is going to correct that for us.

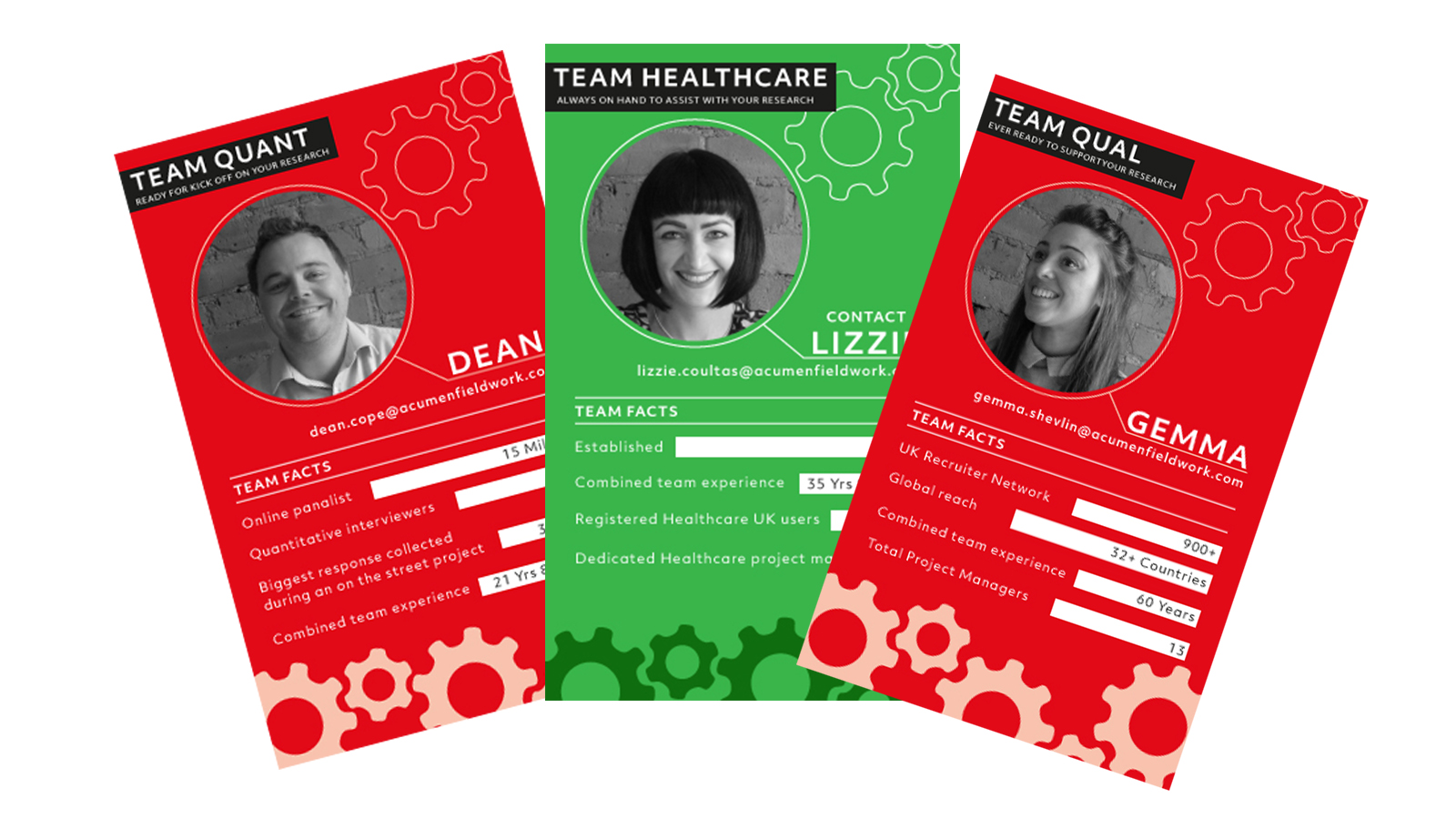

We’ve got some news! The Acumen team is growing with a number of new members […]

READ MORE

We’re delighted to announce that Becki Pickering (formerly Harrison), Fieldwork Director at Acumen, has been […]

READ MORE

We’re all about the data at Acumen – so we decided to turn the lens […]

READ MORE